Analogy of the Road with a Ditch on either side

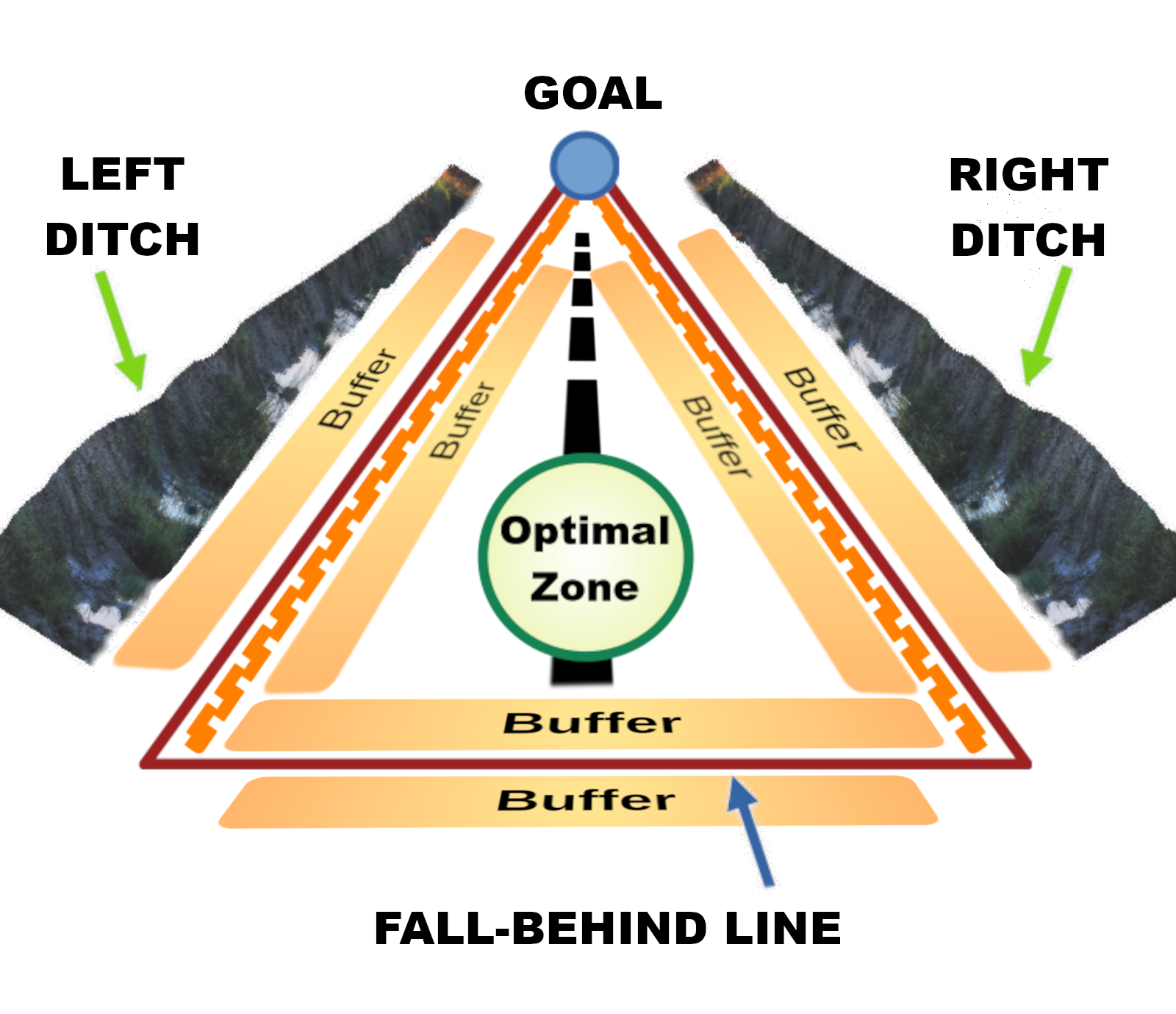

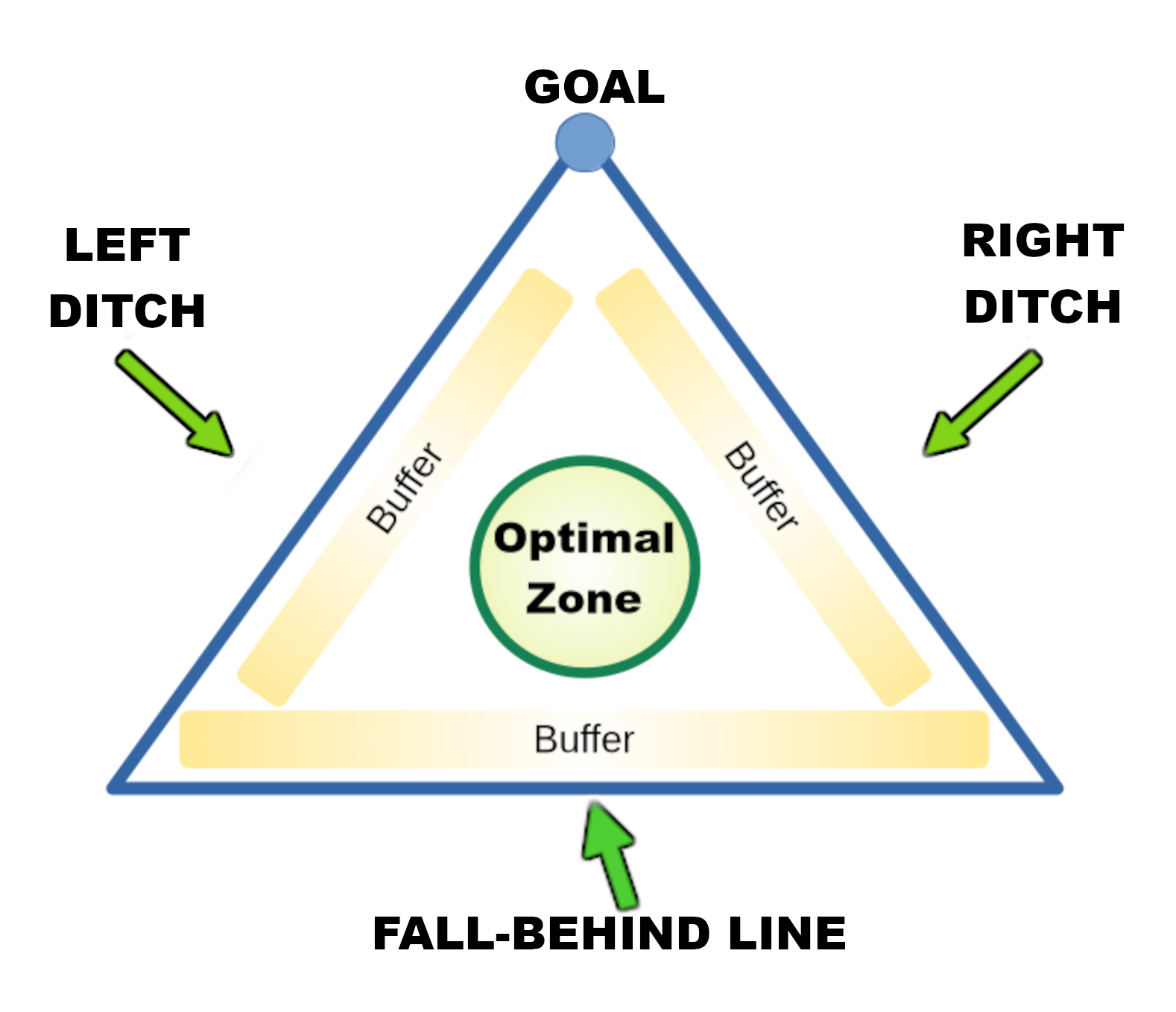

A framework for recognizing where to draw lines before the ditch, remain centered within an optimal zone, and move forward while orienting toward true north.

Analogy of the Road with a Ditch on either side

TLDR: Almost everything we call good has a point where it ceases to be good. When navigating life, relationships, and debates, it is wise to draw lines before things drift into unhealthy extremes. This article proposes a simple cognitive map: draw guardrails before the ditch, set clear markers on the horizon, maintain margin, and keep moving forward. By staying oriented toward a true north, acknowledging the limits of our own perspective, and inviting honest communication and collaboration with others who can see what we cannot, we create space for constructive, long-term solutions.

The Core Concept

For a very long time, I’ve had a very useful (to me) analogy of life being like a road with a Ditch on either side.

Almost everything in life — even good things — has a point where it can go too far, veering off the road into “the ditch” or “off the cliff.” Consider the political left and right. Each side often focuses its energy on arguing against the ditch on the other side of the road. They can become so consumed by this fight that they end up mirroring each other, entrenched in their own ditches, lobbing accusations across the pavement, obsessing over the opposite ditch. An outside observer might conclude that the better path lies somewhere in between — on the road itself. If each side could draw a line just before their own ditch, they could even emerge out of their ditch and also help the other side do the same.

I often even say that if you see only one ditch, there is a very good chance that there is one right behind you.

Continuing with this analogy, then we could say that if we manage to stay on the road, we could have a third option, of moving forward towards a goal. It’s like driving toward a point on the horizon — and the lines on either side keep us from drifting into unhealthy extremes as we go.

Now consider a practical example. The political left often emphasizes helping those at the bottom of society, while the right emphasizes individual responsibility.

The right might say that the left goes too far into enabling people in their process of helping them, to the point where they become perpetual victims and never end up effectively climbing out of their situation. The left might argue that the right created the conditions that led to those people at the bottom, or at the very least that they shouldn’t just leave them behind by only focusing on what was in it for themselves, never realizing the broader consequences of their unregulated decisions.

The wiser path may lie somewhere between these extremes.

For the right, this may mean acknowledging that not everyone can simply “pull themselves up,” and that it would be beneficial to work alongside those on the left who are serious about finding solutions and addressing real needs in practical ways.

For those on the left, this may mean recognizing that current conditions are not entirely the fault of others. Blame and anger, while sometimes understandable, can harden into a desire to “tear everything down.” That impulse can obscure practical solutions and delay the personal and collective empowerment needed to move forward. Progress requires learning how to communicate and collaborate with those on the right, who often possess resources, experience, and practical tools that could help chart a path toward meaningful, long-term solutions.

In a marriage, there is often a “Mom’s side” and a “Dad’s side.” They are most effective when they complement one another’s differences and help keep each other on the road. Both can be right — up to a point. Each perspective can be right — until it goes too far and “into the ditch”.

Continuing the analogy, the road forms a kind of virtual triangle as it narrows toward a goal. The two sides of that triangle represent the guardrails we draw before the ditches. The top vertex represents the goal — but also, and perhaps more importantly, a marker on the horizon: the limit of what we can currently see.

Just as we draw lines before the ditch, there are many situations in life where we must establish a visible marker on the horizon. If we have not reached the ultimate goal by that point, we can at least pause — pull over, refuel, check our instruments, and recalibrate our direction. Beyond that marker, we cannot yet make fully informed decisions because some factors remain outside our perspective.

As Jesus said, each day has its own troubles; we are not meant to worry beyond tomorrow. Yet that does not mean we abandon long-term goals. It simply means we move toward them in stages, respecting the limits of our current sight.

That triangle can also represent the mountain we are trying to climb, in which case, the steeper the mountain, then the road has to zig-zag it’s way up, but even in that case, there is usually a cliff on one side and a rock wall on the other and a point up ahead where the road bends beyond our current perspective.

However at the same time and finally, one could say that there is a sort of imaginary line behind us, that represents falling out of the bottom of the triangle. Things that we need to do now, that we can’t do after a certain point, or things that if we procrastinate or don’t do, or decisions that shouldn’t be neglected in the moment and that there is a cost for neglecting them. While at the same time, if we are falling behind we can recover if we push forward.

Essentially forming sort of an optimal zone hovering above the bottom of this triangle. A zone that should have a buffer before the lines that mark the side of the triangle. Some wiggle room, kind of like the reaction zone around our car as we drive down the freeway. So that we aren’t in such immediate danger of going into the ditch, falling behind, or pushing so hard towards the top vertex to where we are overheating our engine and putting ourselves in danger of the smallest maneuver causing us to crash and rollover.

I find myself using this in pretty much almost every thing I do, decisions I need to make, when I’m advising others… Family, business, church, financial goals, conflict resolution…

Specially conflict resolution:

If I only see one ditch, it causes me to try to do what I can to acquire awareness of the ditch right behind me.

Once I’ve identified both ditches, then try to identify the goal, the point in the horizon I’d like to move forward to, or negotiate orienting the other party to.

Set a point in the horizon, when do I check back in if I haven’t heard back from you…

Establish the zone “falling behind” on the bottom, “By when would you like me to do this?…”

What do we need to leave behind, in order to climb to a higher position?

The Graphic Model

This is meant to be a simple geometric cognitive map, a geometric picture of healthy forward movement under constraint. A triangle of motion, with a circle of optimal positioning inside it.

1. The Road and the Ditches

On both sides are ditches.

If we drift too far left or right, even toward something good, eventually there becomes a point after which, that something is no longer good.

- Confidence → arrogance

- Flexibility → compromise of principles

- Discipline → rigidity

- Urgency → recklessness

The ditches represent excess, unhealthy extremes. The road represents bounded intention. So, ideally we should draw lines before the ditch, similar to what happens on an actual road.

2. The Horizon Makes It a Triangle

The sides visually converge toward the horizon. When you look ahead down a straight road, it appears to narrow to a point — or at least to a place toward which we are heading. The horizon, or other obstacles, set a limit on what we can see. Yet we often mark a spot on that horizon towards our destination, or at the very least, the next point in our journey.

From that perspective, the road forms a triangle:

- The apex is the visible target.

- The sides are the guardrails drawn before the ditch.

- The narrowing reflects increasing precision required as you approach a goal.

This is not a new structure — it’s simply what a straight path looks like when you look forward.

3. The Circular Zone Around You

Where you are standing, there is a conceptual circle.

That circle represents:

- The area we occupy, and what we can touch at arms length.

- Our immediate realm of influence.

- Stability zone.

You want to remain centered with a buffer.

- Margin

- Present awareness

- Sustainable pacing

You don’t want to:

- Hug the left edge.

- Hug the right edge.

- Race so hard toward the horizon that you neglect the ground beneath you.

- Drift so low in effort that you fall behind.

4. The Line Behind You

There is also a trailing boundary — the line of falling behind.

Even on a straight road, time moves forward.

There is a reason highways have a minimum speed requirement.

If you slow too much, procrastinate, avoid too long, or hesitate excessively, you aren’t neutral — you’re losing ground. After that line there is a cost, there are usually consequences or at the very least the increased potential of them.

So progress must exceed that trailing line.

A geometric model of perspective: a triangle of motion, with a circle of optimal positioning inside it.

Combined:

- Extremes — the ditches on either side.

- Guardrails — boundaries drawn before the ditch, which perspective narrows into a triangle as we move forward.

- Objective / True North — the horizon point that defines direction and requires continual realignment.

- Regression boundary — the trailing line of falling behind (minimum forward movement).

- Optimal positioning zone — the circle of stability within the triangle.

- Margin — the buffer that allows adjustment without catastrophe.

Life, decisions, and negotiations resemble traveling down a road bordered by ditches. Progress requires direction, boundaries, orientation, and enough margin to remain stable while moving forward.

This is just common sense dressed up visually.

© 2026 Michael Schmitz

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

You are free to share and adapt this work with attribution. Derivative works must be distributed under the same license.